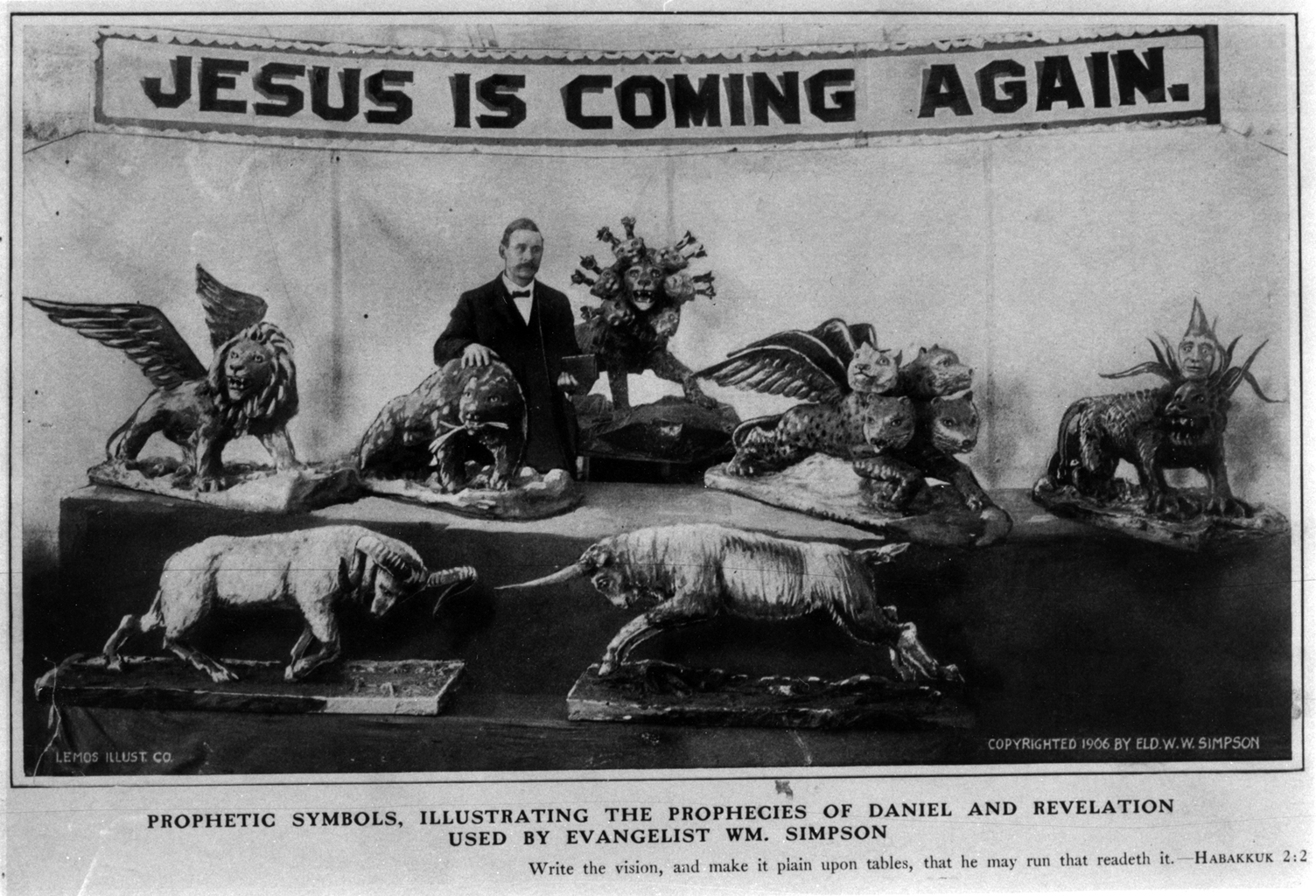

“Write the vision, and make it plain upon tables,

that he may run that readeth it.” Habakkuk 2:2

Visitors to the Center for Adventist Research often remember the papier-mâché beasts from their visit. They are the only things I remember from my visits several years ago as an Andrews University undergraduate student. As you tour the museum at the Center for Adventist Research, these papier-mâché beasts keep a watchful eye from their perch near the ceiling above the display cabinets where they are on permanent display.

You may not be aware of the history of their progenitor, William Ward Simpson, Jr. He was born in Brooklyn, New York August 1, 1872 and died in Los Angeles, April 28, 1907, at the age of 35. His daughter Winea Simpson wrote a biographical sketch of her father. She said “What I knew of my father’s work I learned from Mother and friends who knew my father. I was too young to appreciate his evangelistic talents. However, I do remember him as a happy friendly playful daddy who could balance a broom on his nose and do many other fascinating tricks for his children.”

Soon after he was born, Simpson’s family moved to England, and then moved again, when he was 11, to Florida. He came from an atheistic background. After his father’s death when he was a teenager Simpson found work in Battle Creek. He served first as call-boy in the sanitarium, next as errand boy in the office of Good Health; and afterward he completed an apprenticeship in the Review and Herald office. A series of meetings in the area aroused his interest in the study of the prophecies of the Bible. His growing appreciation of the wonders of Bible prophecy led to his conversion to Christianity. The confidence he had in the Bible, through prophetic fulfillment, caused him to give emphasis to prophecy in his ministry.

His obituary in the Review and Herald, May 23, 1907, states “He was converted in 1890, and not long thereafter, while running a press in the Office, one morning he suddenly stopped the machine and informed the foreman that he was going to leave that work to assist in spreading the light of the third angel’s message in [sic] the earth.”

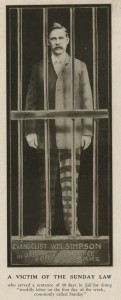

His evangelistic career began in Canada where he studied and developed the techniques which were to draw such large audiences. While ministering in Canada, he was arrested and imprisoned for working on Sunday. He spend 40 days and 40 nights in jail living on nothing but bread and water. He continued serving his apprenticeship in Canada from 1897 to 1902. Simpson writes about his experience in the Review and Herald, May 26, 1896, in an article entitled “From Chatham Jail” and says:

My cell is so small I have hardly room to undress. I am locked in at six o’clock, and let out at seven [the] next morning, so you see that the most of my time is spent there. I am not lonely; for the most precious experiences of my life have been while locked in my cell. Instead of being shut in by bare walls, it seems like being shut in with Jesus.

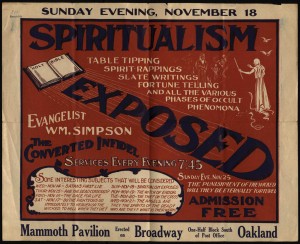

In part because of ill health in Canada and partly in response to Mrs. White’s urging that the cities be evangelized, he moved to southern California in 1902 and conducted campaigns in Redlands, Riverside, Pasadena, San Diego and San Francisco. In 1904 he launched a series of large meetings in the heart of Los Angeles, attracting audiences of as many as 2,000 persons. There were more than 200 adult baptisms as a result of God’s blessing of his Los Angeles effort.

Simpson and family in front of their home in California. The caption written on the card says: “Enjoying the Southern CA Sunshine under our own vine & fig tree.” And also: “Come out in the sunshine. — Will & Nellie”

Mrs. White immediately grasped his success as a shining example of what could be done in large cities. She made him something of a protégé, personally encouraging and instructing him, presenting him to the church leaders as an example to follow.

In a letter dated, September 18, 1904, Ellen White wrote Simpson a letter of appreciation for his work and also gave him advice. “God would have his workers treat their vocal organs with special care, as a precious gift from Him. These organs are not to be abused by over-taxation.” Later in the letter she says:

“I am deeply interested in your work in Southern California. I am so anxious that you shall not break down under the strain of the long, continuous effort. Let someone connect with you who can share your burdens. This is the path that was followed by the great teacher. He sent His disciples out two and two.”

In a letter dated, December 4, 1906, Ellen White wrote William Simpson,

I am pleased with the manner in which you have used your ingenuity and tact to provide suitable illustrations for the subjects you have to present,—representations that have a convincing power. Such methods will be used more and more in this closing work. I wish that you might have a portable meeting house. This would be much more favorable for your work than would a tent, especially in the raining season.

But tragedy struck. In 1907 Simpson died at the age of 35—the first recognized “city evangelist” of the Adventist denomination. Roderick S. Owen writes in Simpson’s obituary in the Review and Herald, “His death was a great shock to all, and it is one of the many things which we are called upon to meet, but are unable to explain.”

Simpson took the Habakkuk 2:2 bible text as his tag line “Write the vision, and make it plain upon tables, that he may run that readeth it.” His special emphasis on prophecy and his desire to make it easy for people to understand kept him innovating methods to reach people with the prophetic message. He was an effective evangelist that drew large crowds. He used innovative means for marketing his meetings.

In a letter dated November 6, 1906, Ellen White wrote to F. E. Belden “He [Simpson] has large life-like representations of the beasts and symbols in Daniel and the Revelation, and these are brought forward at the proper time to illustrate his remarks.”

The papier-mâché beasts that Simpson used in his evangelism efforts were still used by evangelists after his death. Simpson had used them by bringing them up out of a background. Beveridge R. Spear relates that he and other evangelists during the 1930s in the southwestern United States used them differently than Simpson. “Instead we drew them across the stage on tiny castors with a spotlight on each one as its turn came to appear in the lecture.” This was an impressive and effective visual aid for the audience. After this extensive use in many tent meetings the beasts were in danger in the late 1940s of being taken to the dump. However, they were saved from that fate, and after being transferred around to several places, they ended up at Andrews University in the late 1970s and have been on permanent display ever since.

The Center for Adventist Research has a collection of materials related to Simpson which can be found in Collection 81.

Katy Wolfer, Special Projects Manager / Pins articles about the etmology of the word “you” to her Pinterest board: Interesting.